It is a truth universally acknowledged by every war correspondent, humanitarian aid worker, and Western diplomat: Some wars, like Syria’s, receive tremendous public attention, which can translate into pressure for resolution. But many others, like Yemen’s still raging but much-ignored conflict, do not.

Some of the reasons are obvious; the scale of Syria’s war is catastrophic and much worse than Yemen’s. But attention is about more than numbers. The conflict in eastern Congo, for instance, killed millions of people and displaced millions more, but received little global attention.

Every country in the world has its own version of that dynamic, but it is uniquely significant in the United States.

The United States is the world’s sole remaining superpower, but Americans often seem so inward-looking as to be almost provincial. Foreigners often express wonder that US television news, for instance, spends fewer minutes covering the rest of the world than the rest of the world’s news shows spend covering the United States.

A result is that American attention seems both vitally important and frustratingly elusive.

But when the world asks why the United States has forgotten Yemen and other conflicts like it, that has the situation backward. The truth is that inattention is the default, not the exception.

Conflicts gain sustained American attention only when they provide a compelling story line that appeals to both the public and political actors, and for reasons beyond the human toll. That often requires some combination of immediate relevance to US interests, resonance with US political debates or cultural issues, and — perhaps most of all — an emotionally engaging frame of clearly identifiable good guys and bad guys.

Most wars — including those in South Sudan, Sri Lanka and, yes, Yemen — do not, and so go ignored. Syria is a rare exception, and for reasons beyond its severity.

The war is now putting US interests at risk, including the lives of its citizens, giving Americans a direct stake in it. The Islamic State has murdered American hostages and committed terrorist attacks in the West.

And the war offers a compelling tale of innocent victims and dastardly villains. The Islamic State is a terrorist organization with a penchant for crucifixions and beheadings. President Bashar Assad of Syria and his patrons in Iran are hostile to the United States and responsible for terrible atrocities. And now Russia, which is at best America’s frenemy, is fighting on their side as well.

The Obama administration’s refusal to bomb Syria in 2013, and subsequently to intervene more fully, has also made this a domestic political dispute, giving politicians on both sides an incentive to dig in. This provided an appealing focal point for election-year political debates over Obama’s foreign policy and for how to assign blame for the Middle East’s collapse. Those debates have sharpened and sustained domestic attention on Syria, giving both the public and politicians reason to emphasize the war’s importance.

But it is rare for so many stars to align.

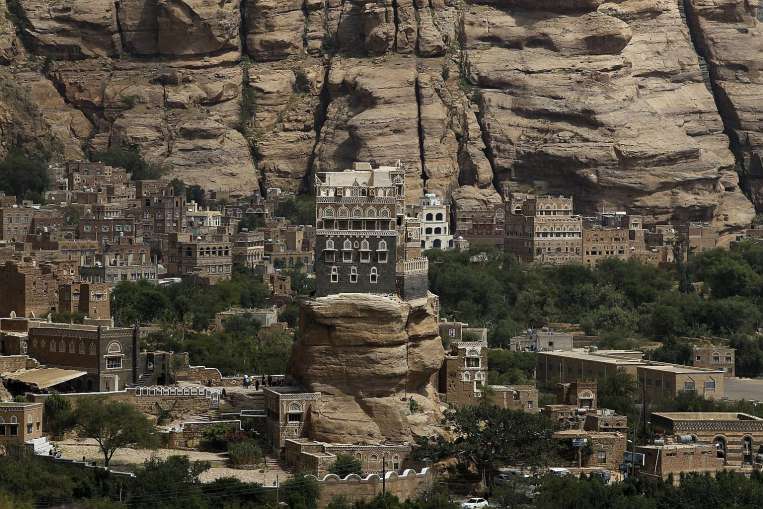

Yemen’s death toll is lower than Syria’s, and although Al Qaeda does operate there, Yemen’s conflict has not had the kind of impact on US and European interests that Syria’s has. There is no obvious good-versus-evil story to tell there: The country is being torn apart by a variety of warring factions on the ground and pummeled from the air by Saudi Arabia, a US ally. There is no camera-ready villain for Americans to root against.

The war’s narrative is less appealing to US political interests. Yemen’s Houthi rebels pose little direct threat that American politicians might rally against. On the other side of the conflict are Saudi airstrikes that are killing civilians and targeting hospitals and aid workers, at times with US support.

No American politician has much incentive to call attention to this war — which would require either criticizing the United States and a US ally, or else playing up the threat from an obscure Yemeni rebel group. It is little wonder that, when several senators recently tried to push a bill to block arms sales to Saudi Arabia over its conduct in Yemen, they found only a few sponsors and the motion was tabled in a 71-27 vote.

It is rare but not impossible for far-off wars to cross the threshold to gain national attention. The crisis in Darfur, Sudan, for instance, became a national cause célèbre in the early 2000s even though it had little direct effect on US interests.

But Darfur offered a simple and compelling story: that dictator Omar al-Bashir and his henchmen were committing genocide against innocent civilians, and that the United States could stop them. That seemed to offer a way for Americans to atone for their failure to stop the Rwandan genocide a decade before, and to prove that they had learned the right lesson from that horrifying atrocity. That made for an appealing narrative and an appealing cause.

The conflict also fit the domestic political debate at the time. The slogan “Out of Iraq, Into Darfur” presented intervention in Darfur as an alternative to President George W. Bush’s pre-emptive war in Iraq, and was a frequent feature on signs at anti-Iraq-War protests. “Saving” Darfur came to symbolize an alternative vision of US power that appealed to those who did not agree with Bush’s policies but also did not want the United States to withdraw into isolation.

But Darfur, like Syria, has proved to be the exception rather than the rule.

Today there is little awareness of South Sudan’s continuing catastrophic collapse or the Central African Republic’s civil war. The civil war in Somalia simmers into its third decade, barely noticed.

Most conflicts are Yemens, not Syrias or Darfurs.