For months, the front lines of Yemen’s civil war have been fairly stagnant. But on Jan. 7, Yemeni troops backed by Emirati forces began to advance on the city of Dhubab, near the Bab el-Mandeb strait. The stated objective of the operation, known as “Golden Arrow,” is to secure Yemen’s western coastline in Taiz province in the hope of blocking any further arms deliveries to Houthi rebels and supporters of former President Ali Abdullah Saleh. However, the offensive will also greatly reduce the risk of anti-ship missile attacks against vessels transiting the waters off Yemen’s coast.

Airstrikes in Dhubab by the Saudi-led coalition began to intensify in the last week of December 2016. Coupled with separate reports of the Emirati air force’s frequent use of precision-guided munitions in the area, these attacks seem to have been part of a preparatory air operation ahead of the ground assault on the city. Despite these efforts, however, Yemeni and Emirati forces have suffered substantial losses in men and material since moving in on Dhubab. According to unconfirmed reports, Houthi fighters have already destroyed as many as 15 armored vehicles in the offensive. Some claims also suggest that Houthi snipers have targeted several high-ranking officers among their opponents’ troops.

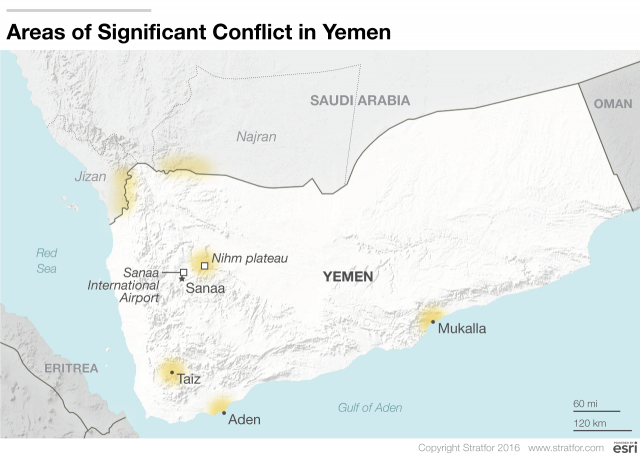

The offensive is moving forward in spite of these losses. The main unit of Operation Golden Arrow has circumvented Dhubab and is now pushing farther north toward the city of Mocha. Its progress has been slowed considerably by land mines that Houthi fighters and Saleh loyalists laid north of Dhubab, as well as by staunch resistance near several military positions in the area. Nevertheless, Yemeni troops and their Emirati backers have committed a considerable number of forces to the operation, and five full brigades are reportedly engaged in the fight.

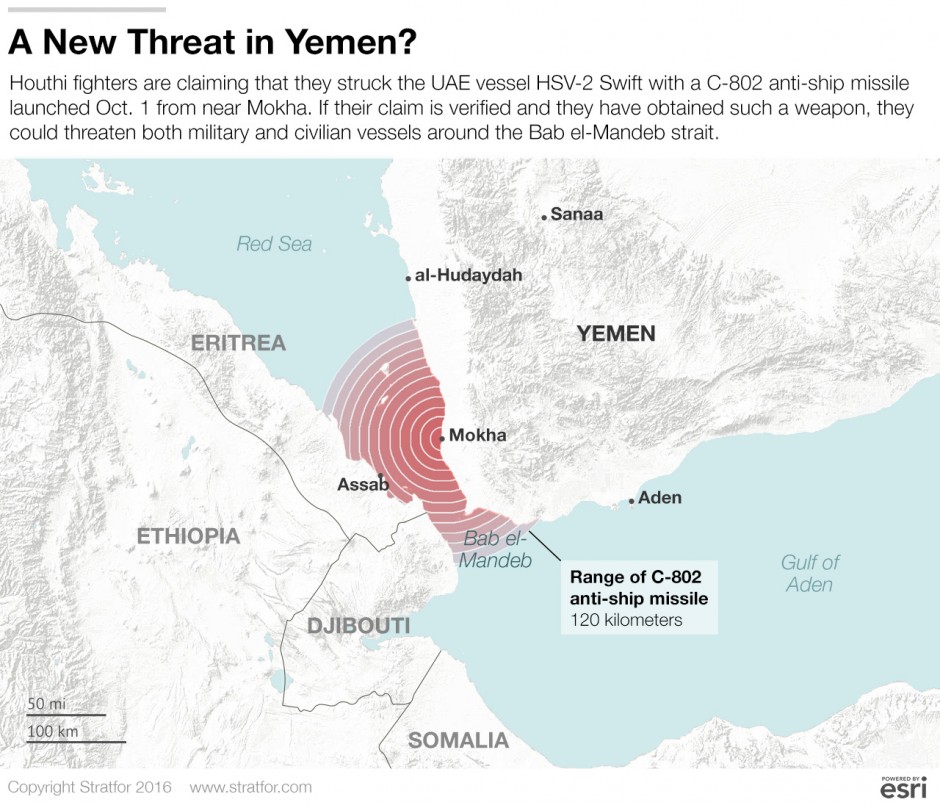

Though the true intentions behind the offensive are still unknown, the descriptions that have been released suggest that troops do not plan to move much farther beyond Mocha. Therefore, it is unlikely that the march will continue north to free the larger port city of al-Hudaydah. But the operation will have an impact on the areas around Dhubab and Mocha. Recent anti-ship missile attacks against Emirati, Saudi and U.S. naval vessels as well as an Iranian-flagged cargo ship allegedly originated in these regions. Gaining control over Taiz province’s coastline will help prevent similar attacks along the Bab el-Mandeb strait in the future, making the waters much safer for civilian shipping and naval vessels supporting operations conducted in Yemen.

Meanwhile, front lines located elsewhere in Yemen have remained relatively stable. Government and coalition forces have made some small advances, particularly in the city of Taiz and near Bayhan. Should Operation Golden Arrow prove successful, it could help government-aligned troops in Taiz secure more victories. However, fighting in the country’s mountainous regions will progress more slowly than in the flat coastal lands. Overall, the Saudi-led coalition continues to make gradual but steady gains, though the limited commitment of the coalition’s members has dragged out its operations. The alliance’s persistent pressure on Houthi fighters and Saleh loyalists has exacerbated the pre-existing tensions between the two groups: Over the past month, the Houthis have been at odds with Saleh’s supporters, particularly the Republican Guard. Such frictions are likely to worsen while the rebels’ situation remains dire.

Beyond the protracted conflict in Yemen’s central mountains and on its western coast, signs of stability are beginning to emerge in other parts of the country. Just last week, Glencore — a large international crude oil trader — arranged for an oil tanker to transport a shipment from an unknown Yemeni terminal as early as Jan. 15. (The terminal is most likely located in Ash Shihr, where the Yemeni government sold 3 million barrels of crude to Glencore last summer.) These continuing oil exports, though few and far between, indicate some level of confidence in the stability of Yemen’s Hadramawt region, including the cities of Mukalla and Ash Shihr. Oil shipments ground to a halt in early 2015 when the Saudi-led coalition intervened in Yemen. But now that Yemeni troops and their allies have regained control over Mukalla and its surrounding region from al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, and a second crude sale has been made, it appears that the Yemeni oil sector is beginning to come back online.

Nov. 18: Hopes of a Cease-Fire Are Quickly Dashed

Hopes for a new cease-fire effort in Yemen arose earlier this week after U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry’s two-day visit to Oman, but they were quickly dashed. Given the heavy fighting still raging in Yemen and the disagreements among members of the Saudi-led coalition backing embattled President Abd Rabboh Mansour Hadi, the failure of the renewed push for peace was hardly surprising. Kerry announced Nov. 15 that representatives of the Houthi alliance fighting to supplant Hadi had agreed, after an hourslong meeting, to a cease-fire and to join a national dialogue working toward a unity government. But the tentative step toward a cease-fire, reported by the media at midnight on Nov. 17, came and went without a notable pause in the violence.

Hadi’s foreign minister, Abdulmalik al-Mekhlafi, said the Yemeni government rejected the overtures and had not agreed to any new dialogues or plans for a unity government. He also questioned the relevance of the talks between Kerry and the Houthis, saying that no coalition representatives had been present. The refusal of the Hadi government to engage in a national dialogue stems from its reticence to cede power without guarantees that the Houthis will give up their weapons and territory. In addition, it rejects the legitimacy of the Supreme Political Council put together by the Houthis and exiled President Ali Abdullah Saleh’s General People’s Congress (GPC) party to stand as part of a unity government.

Disagreements over strategy among the Saudi-led coalition supporting Hadi have kept the cease-fire discussions from gaining traction as well. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates do not see eye to eye on how to manage their southern neighbor’s civil war. Stratfor contacts indicate that in recent months, Saudi Arabia has worked to erode the United Arab Emirates’ influence in Aden, the Yemeni port city it helped to recapture last year. One of the ways in which the Saudis wield influence in Yemen is through the Islamist Islah party, which commands power in Aden and elsewhere. But the United Arab Emirates is opposed to Riyadh using the group to advance its own agenda, which has meant Abu Dhabi’s sway has declined in areas of the country where the Islah party is dominant.

The quiet fight for influence between the Saudi and Emirati governments is indicative of both countries’ security concerns and differing views on how to approach them in the long term. The United Arab Emirates reportedly supported the latest U.N.-backed peace plan even though Saudi Arabia did not, a stance that was clearly reflected in al-Mekhlafi’s refusal to sign off on any new peace process.

As attempts to broker peace talks falter, violence in Yemen continues unabated. Combat on the Yemen-Saudi Arabia border has remained constant, despite Riyadh’s concerns about the conflict spilling over into its territory. Houthi fighters are moving closer to the Saudi border city of Najran, which suffers from occasional collateral damage from crossfire. Farther south, fighting continues to rage in the city of Taiz, where casualties often include civilians. Within Taiz, fighters allied with Hadi government forces have engaged in intermittent battles with Houthi-GPC forces on multiple fronts. Fighting this week centered on an attempt to wrest control of the Republican Palace to the east of Taiz from Houthi forces. Although the pace of coalition airstrikes reportedly eased earlier in the week, bombings in Taiz, Saada province and the capital of Sanaa have continued unabated.

Oct. 12: A Second Missile Attack Threatens to Drag the U.S. Further Into Conflict

For the second time in a week, anti-ship cruise missiles (likely the Chinese designed C-802 or an Iranian equivalent) targeted U.S. Navy vessels from Houthi-controlled territory in Yemen. On Oct. 12, the USS Mason fired defensive salvos in response to two missiles that failed to strike it. The same vessel was targeted Oct. 9 and reportedly fired three missiles in defense of itself and of the USS Ponce, which it was escorting. After the Oct. 9 attack, Houthis denied that they had targeted the vessels, but U.S. officials say the evidence implicates the group. Both times, the USS Mason was cruising on the Red Sea along a critical international shipping route just north of the Bab el-Mandeb strait.

Though it is almost unprecedented that U.S. warships would be shot at by anti-ship cruise missiles launched from onshore batteries (the only other known instance was when the USS Missouri battleship was targeted during the Gulf War), the Houthis hardly pose a threat to the United States. It would be difficult for them to break through the U.S. Navy’s multiple defenses with their relatively unsophisticated targeting systems and equipment. Still, such brazen attacks make a U.S. military response almost inevitable, dragging the country deeper into the conflict in Yemen that it has been working to distance itself from. In fact, although the Pentagon was hesitant to confirm details about the first missile strikes this week, a U.S. Navy official warned that “anyone who fires against U.S. Navy ships operating in international waters does so at their own peril.”

When it comes to Yemen, the United States is in a tough spot politically. It supports the Saudi-led coalition fighting Houthi rebels and forces loyal to former Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh but has recently distanced itself from the coalition because of intense international scrutiny on its tactics and high civilian casualties. Though Washington conducts drone attacks and special operations forces strikes in southern Yemen against al Qaeda targets, it has restricted its support for the Saudi-led coalition since the war began in 2015 to an advisory role with logistical assistance. The latest naval attack could change that dynamic; it clearly necessitates a U.S. response, but if the United States strikes Houthi targets, it will be interpreted by many Yemenis as a sign of full U.S. alignment with Saudi Arabia. And inconveniently for Washington, the dilemma comes at a time of increased scrutiny in Congress on the level of U.S. cooperation with Saudi Arabia in Yemen.

Sept. 22: The Houthis’ Grip Over Sanaa Is as Strong as Ever

Two years have passed since Houthi rebels from the Saada highlands seized control of Yemen’s capital, Sanaa, but still the battle for the city rages on. Several recent developments show just how entrenched the Houthis are in the area. On Sept. 20, Houthis kidnapped an American teacher from the English language school he ran in the city, and they are reportedly holding him in the Central Security Bureau, a building formerly under the Yemeni government’s jurisdiction. The incident reflects the degree of control the Houthis continue to have over Sanaa’s security.

Perhaps more important though, Yemen’s internationally recognized president, Abd Rabboh Mansour Hadi, ordered Sept. 17 that the country’s central bank be moved from Sanaa to the southern city of Aden. The bank’s former governor has been adhering to the government’s decision and is willing to transfer power to his newly appointed replacement. The Houthis, however, refused to comply and instead froze the bank’s assets. Currency traders and financial executives throughout the capital have held a flurry of meetings to try to sort out the conflicting orders, and international entities such as the World Bank have lent their support to Hadi, though they have stopped short of intervening outright on his behalf.

The embattled president is attempting to financially cut off the Houthis while making it easier for Saudi Arabia to directly deposit funds into the foundering central bank’s reserves — something that would be nearly impossible if the bank were to remain in Sanaa. Houthi officials have insisted that the decline in bank reserves from $5.2 billion in September 2014 to $700 million in August 2016 can be explained by imports of critical supplies and food. After all, Yemen imports the bulk of what it consumes, although the country’s trade has become more complicated amid the protracted civil war. On Sept. 20-21, Houthi leaders urged their followers to deposit at least 50 rials (about $0.20) into the central bank to demonstrate the Houthis’ popular appeal and political strength. They may also be hoping to withdraw as much money as they can before the bank begins the complicated process of closing its doors and moving its operations southward.

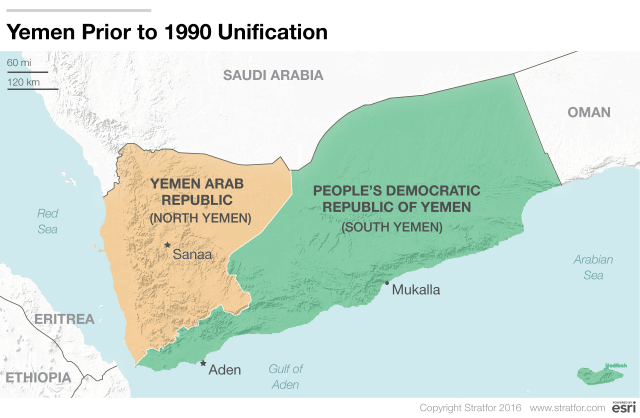

The Houthis’ staunch resistance to the bank’s relocation hints at the deepening divide between Yemen’s north and south, as well as to the desire of external patrons such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates to bolster Aden’s security and political capital. But building up the southern city will not be easy. Hadi’s support in the northern and southern regions is diminishing, as are Saudi Arabia’s chances of becoming the savior of the Yemeni economy as it continues to bomb civilians and infrastructure across the country. The United Arab Emirates, meanwhile, is increasingly washing its hands of the conflict in the north, focusing instead on strengthening its patronage networks in the south. The Southern Movement, desperate to preserve its clout in the southern secessionist cause, has called for the formation of a political council that would merge the disparate resistance factions scattered throughout southern Yemen. Though a tall order, the call is notable because of the southern fighters’ enduring role in combating al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, as recent skirmishes in Abyan province attest.

In the meantime, Yemen’s war continues unabated, in spite of discussions in the U.N. Security Council about the conflict’s ideal political resolution. Clashes in Marib, Taiz, Lahj and Nehim have prevented either side from advancing the front lines in any notable way. Border skirmishes, however, remain a concern for Saudi Arabia, particularly since Houthi forces captured more high ground around the Saudi city of Najran. Even so, a deeper Houthi incursion into Riyadh’s territory is unlikely, considering the devastating military response such an offensive would invite.

Aug. 22: When Peace Negotiations Fail

After months of peace negotiations, Yemen’s politics look more divided than ever. On Aug. 13, in an effort to unify the country, parliament voted to approve a joint political council proposed by leaders from the Houthis and the General People’s Congress. Since that initial parliament session, the first in two full years and the first since Houthis moved to occupy Sanaa in September 2014, the council has tried to govern from its base in Sanaa, but all it has accomplished is to polarize the country more.

Hundreds of thousands of citizens marched through Sanaa on Aug. 21 in support of peace and the Houthi-General People’s Congress alliance, but there are just as many throughout the country who decry the actions of the council. Internationally recognized Yemeni President Abd Rabboh Mansour Hadi, with the support of the Saudi-led coalition, has loudly protested the formation of the council and its subsequent actions. In a meeting with U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs Anne Patterson on Aug. 18, Hadi went so far as to call the Houthi-General People’s Congress alliance an evil threat. Hadi and those lawmakers who support him say the Aug. 13 parliamentary session that created the alliance was completely invalid because it did not meet quorum, but that claim has been found to be untrue.

On the Ground

Hadi’s forces have made a number of small territorial gains in the past couple of weeks, with the aid of Saudi airstrikes, which ramped up after peace talks fell apart in early August. Government forces managed to reclaim some territory in Taiz city Aug. 19, particularly in western parts of the city, where some of the fiercest battles between pro-Houthi and government forces have taken place. The southern road out of Taiz toward Aden remains hotly contested between government, Houthi and southern resistance forces. Southern resistance fighters allied with Hadi’s forces are reportedly in control of the road. Another critical road that remains contested is the one into Sanaa from the northeast district of Nehim, where the government forces have taken a number of small, mostly uninhabited hills near the airport in recent weeks.

Government forces did manage to clear portions of Abyan province from al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula control Aug. 14, but, though dozens of casualties were reported in the course of the assault, they have surely managed to displace militants from only a small amount of territory. Government forces also defeated a small cell of Islamic State-affiliated militants in Lahij province.

International Response

Humanitarian concerns reached somewhat of a public apex with an airstrike that resulted in 19 casualties on a Doctors Without Borders hospital in northern Saada on Aug. 15. The group announced its withdrawal from Yemen later the same week. A critical bridge for food delivery from al-Hudaydah port into Sanaa was bombed Aug. 11 as well.

Coming up this week, two international meetings will focus on the next steps in attempting to resolve the seemingly intractable crisis. The U.N. Security Council will meet in New York to focus on Yemen, and the U.S., British and Gulf Cooperation Council foreign ministers will meet in Jeddah on Aug. 24-25 with a focus on Yemen and Syria. One subject for discussion will be Russia’s role in the conflict.

Talks will include Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Mikhail Bogdanov and Saudi Deputy Crown Prince and Defense Minister Mohammed bin Salman, as well as the U.N. envoy to Yemen and the Yemeni foreign minister. Russia, which officially backs Hadi’s government, raised eyebrows in August when it protested a U.N. Security Council resolution on Yemen that condemned the Houthi actions. Houthi-backed former Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh asked Russia on Aug. 21 to utilize Yemeni air bases in the pursuit of joint anti-terrorism goals. Though it is highly unlikely that Russia would ever risk its relationship with Saudi Arabia by responding to the request or by helping Saleh’s forces, Russia has indeed walked a fine diplomatic line with respect to Yemen.

Finally, the revelation last week that the United States pulled its personnel assigned to advise the Saudi airstrike campaign from Saudi Arabia does not indicate that the United States has retracted all support for the campaign. It does, however, signal a significant reduction in personnel support. It is possible, given that airstrikes have increased since dipping in June, that the United States has already or will again increase its support for the coalition. Given that airstrikes were significantly lower in June, the reduction in personnel made sense.

Aug. 3: Peace Eludes Yemen’s Warring Parties

The clock is ticking on a Yemeni peace deal, but with less than a week left and many issues still unresolved, an agreement is unlikely to be reached. In late July, the Foreign Ministry of Kuwait — the country hosting Yemen’s negotiations — gave the parties involved an ultimatum: Strike a deal by July 29 or go home. Instead, both sides dug in their heels and clung to their demands, refusing to compromise. When it became clear that common ground would not be found by Kuwait’s deadline, the U.N. envoy to Yemen scraped together a last-minute extension, securing another week for the delegations to haggle with each other. The move appeared to pay off when, on July 31, Yemen’s foreign minister signed on to the United Nations’ proposal for ending the country’s civil war.

But aside from briefly delaying the talks’ conclusion, and perhaps staving off a rapid escalation in fighting, the victory is hollow. A true deal can be made only if both sides agree to it, and the delegation comprising Yemen’s Houthis and supporters of former President Ali Abdullah Saleh has shown no sign of supporting the U.N. resolution by the new Aug. 7 deadline. Moreover, on July 28 they formed their own 10-person power-sharing council, the Supreme Political Council, meant to take the place of the Houthis’ Revolutionary Committee. Though appointments to the new body have not been announced, it will reportedly include two generals and three civilians from each of the Houthi and Saleh-led parties.

The Houthis and Saleh’s backers are withholding support for the United Nations’ peace terms, which include the surrender of arms and a retreat from certain cities under the Houthis’ control. Yemeni President Abd Rabboh Mansour Hadi and his Saudi patrons, meanwhile, refuse to recognize the legitimacy of the new Supreme Political Council. The resulting stalemate makes it clear that the peace talks have a long way to go before they can achieve any sort of resolution.

In the meantime, the Houthis and Saleh’s forces have renewed their demands to negotiate with the Saudis directly, claiming that the Yemeni government representatives attending the talks are not powerful enough to make a deal. And in a way, those demands have been met: A group of ambassadors to Yemen from various countries, including Saudi Arabia, participated in the talks on Aug. 2. At the same time, the Yemeni government delegation left for Riyadh, claiming that the negotiations had little value (and hoping that the U.N. Security Council will pressure the Houthi and Saleh forces to sign on to the U.N. agreement instead).

On the ground, Hadi-led forces have seized territory around Mount Qadhaf and Mount Dhahir, and fighting on the Nihm Plateau continues. The warring sides also clashed in al-Jawf on July 31, while heavy airstrikes and ground fighting persist in Taiz. Conflict on the Yemeni border in the Saudi regions of Jizan and Najran is ongoing, having intensified over the past few weeks. Saudi Brig. Gen. Ahmed al-Asiri issued a statement to the Houthi and Saleh-led forces on July 31, calling the uptick in border violence a “red line.” It is unclear, however, what Riyadh’s response to the breach of that red line will be aside from more airstrikes. Of greatest concern is the potential for higher levels of violence in Sanaa; skirmishes were reported near the city’s airport late on Aug. 2.

Finally, sporadic activity by the Islamic State and al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) has continued in Yemen’s restive southern and central regions, despite the Yemeni army’s July 29 offer to pardon any militants who turn themselves in within two weeks. On July 30, an Islamic State media outlet claimed responsibility for the assassination of a police officer in Aden, and on Aug. 2, Yemeni troops apprehended AQAP militants planning a coordinated attack on Mukalla. Since the country’s peace talks are nowhere near complete, the violence and heavy fighting will undoubtedly continue.

July 21: A Deadline for Peace in Yemen

Yemen’s warring factions are coming up against a deadline. Representatives of both sides have been mired in peace talks in Kuwait for three months. Now, Kuwaiti Undersecretary for Foreign Affairs Khaled al-Jarallah has told the parties that they must reach an accord by the first week of August or be expelled from the country. U.N. special envoy to Yemen Ismail Ould Cheikh Ahmed said July 16 that the next two weeks of talks could be Yemen’s last chance for peace, at least according to the shaky framework set up three months ago.

But a peace agreement has remained elusive, and both sides are becoming increasingly frustrated. Houthi rebels allied with former Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh are demanding direct talks with Saudi representatives, who have a great deal of influence over the followers of President Abd Rabboh Mansour Hadi. Saudi Arabia is also the primary force in the coalition launching airstrikes in Yemen. But while Riyadh is backing Hadi’s delegation in the Kuwait talks, the Saudi government itself has little presence in the negotiations. Even so, the Houthis believe that the Saudis are the ones who have the real decision-making power.

The actions of Houthi forces on the ground indicate that their leaders likely believe the talks will amount to nothing. A Houthi spokesperson issued an ultimatum July 19: Houthi border offensives will continue until Saudi airstrikes halt. And indeed, cross-border shelling by militants into Saudi Arabia’s southern districts, including Jizan, have increased. In response, troops loyal to Hadi have launched an offensive into Hajja province in northwest Yemen to erode the Houthis’ ability to carry out attacks in the Saudi regions of Jizan and Najran. They now reportedly hold the city center of Harad District in Hajja.

The battlespace is made more complicated by the fact that the militants operating under the umbrella of both parties often act independently of the negotiating representatives in Kuwait City. For instance, in the past few weeks, rebel groups struck a local bilateral agreement with Hadi loyalists to allow for the provision of urgently needed aid. This suggests that even if a deal is made in Kuwait, individual factions might not adhere to it.

In fact, some groups are attempting to build up local loyalties in anticipation that the Kuwait talks will be ineffectual. In Taiz, for instance, the chief of the Houthi Revolutionary Command ordered militants to provide medical care for residents. In the south, the United Arab Emirates has focused its strategy on giving the population aid while targeting al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. For its part, the local al Qaeda affiliate has managed to thrive and establish a stronger hold in the southern portion of the country, providing its own assistance to local populations. The United States and the United Arab Emirates have discussed the dire need to back more counterterrorism operations in the south, and U.S. Army Gen. Joseph Votel announced July 15 unspecified plans to deploy more U.S. forces to Yemen to help such counterterrorism measures.

The forces loyal to Hadi now face two choices. In the coming weeks, they could launch an offensive to seize control of the capital, Sanaa, which is now in the hands of Houthi rebels and Saleh’s troops. A decision to do so would lead to fierce fighting with rebel forces. (Though the United Arab Emirates is still part of the fight, it is primarily focused on building up relationships and stabilizing the precarious security situation in southern Yemen.)

Alternatively, Hadi could decide to strike a deal in Kuwait in the next two weeks. Doing so would mean accepting that each step of the negotiating process will be slow and arduous. Implementing the key demand that the Houthis leave occupied cities and surrender their weapons, for example, would first require establishing provisional ruling councils.

Regardless of what Hadi’s side chooses, the outcome will depend on what the Houthis and Saleh deem acceptable. And even if the two parties align, there is little guarantee that the disparate militant factions on the ground will abide by their decision.

June 17: The Beginning of the End of UAE Involvement

Throughout Yemen’s civil war, the United Arab Emirates has contributed ground forces to the Saudi-led coalition backing the government against the Houthi insurgent movement and fighters loyal to former President Ali Abdullah Saleh. Now, the UAE armed forces are shifting their military role in Yemen. The commander of the UAE armed forces announced June 16 on Twitter that the war in Yemen “is practically over” for his country’s ground forces.

The announcement was light on details, sparking speculation before more information surfaced. Other UAE officials clarified that the country will continue to be a capable and honest Saudi ally in Yemen, suggesting that it is not planning to withdraw.

Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have different preferred local partners in Yemen. For instance, Saudi Arabia has collaborated with the Islah party, a Muslim Brotherhood affiliate in Yemen. The United Arab Emirates, which has been active mostly in south Yemen, has balked at this partnership, allying instead with the separatist Hirak and Southern Resistance movements. The June 16 statements referred to a UAE transition to security and assistance, which could mean that the country’s local partners will assume the lead role in direct combat, with UAE forces backing them up.

Like Emirati participation, most Yemeni military ground activity has occurred in southern Yemen. Forces there have tried to secure the port city of Aden while supporting the Southern Resistance in its effort to expel al Qaeda from population centers under the militant group’s control. Riyadh, meanwhile, is more concerned with northern Yemen, interpreting the Houthi movement as a direct threat to Saudi interests and partnering with Islah to quash it.

Most of the fighting in southern Yemen has died down. Reconstruction and mopping up the remnants of al Qaeda are now the main order of business. But clashes rage on in the north, where Houthi forces are mounting a fierce resistance in Taiz, Sanaa and al-Hudaydah. The UAE commander’s initial announcement, therefore, was an admission by the United Arab Emirates that the conflict it cares about is winding down. Follow-up statements explained that the United Arab Emirates will likely continue security operations in southern Yemen to avoid a resurgence of al Qaeda forces. Even so, with less at stake in northern Yemen, UAE forces will probably avoid direct involvement in the ground operations moving on Sanaa.

June 4: Peace Talks Yield Gradual Progress

Peace talks are slowly unfolding in Kuwait City, but fighting in Yemen continues unabated. In some areas, including the country’s central regions to the east and southeast of Sanaa, the conflict has even intensified over the past few weeks. The provinces of Marib, Shabwa, Dali and Nehim have been largely unaffected by the loose cessation of hostilities that was supposed to blanket Yemen for the duration of negotiations. Fighting along the country’s border areas has lingered, too. Saudi Arabia intercepted a missile fired from Yemen on May 30, and several skirmishes were reported in the Najran area earlier in the month. For the most part, the cease-fire has only tenuously held in Sanaa, where the pace of Saudi airstrikes has slowed considerably since talks began in mid-April.

The persistent fighting can be attributed in part to the Houthi rebels, who are trying to seize as much territory as possible should negotiations lead to a deal that could erode their standing in Yemeni politics. The rebels have made piecemeal gains in northwest Shabwa, including recapturing parts of Usaylan from coalition forces. They are also vying for control Bayhan, which lies near a critical road to Sanaa.

The presence, however, of militants belonging to Yemen’s Southern Movement, known colloquially as Hirak, has added to the instability in Shabwa, Taiz and Aden to the south. Though the organization initially aligned itself with the coalition of forces backing Yemeni President Abd Rabboh Mansour Hadi, the relationship between the two is marred by constant tension. The internal feud boiled over on May 31 when coalition security forces clashed with Hirak fighters who swarmed a security administration building in Aden.

Meanwhile, in southern Hadramawt and Lahj, raids led by the United Arab Emirates against al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) have become less frequent. But Abu Dhabi’s mission to clear the group’s members from positions of authority in the province and reduce their territorial holdings is not over. Attacks by AQAP and the Islamic State continue to endanger Yemen’s southern cities. On May 15, an assault on Mukalla left 47 people dead; a week later, an attack in Aden killed dozens of Yemeni army recruits.

Despite the ongoing violence, there are some indications that Yemen’s peace talks may be yielding fruit, however slowly. Hadi’s coalition continues to insist on full adherence to U.N. Security Council Resolution 2216, which requires the Houthis to surrender weapons seized from the state and withdraw from all of their territorial holdings. On June 2, a Houthi spokesman expressed the rebels’ willingness to lay down their weapons, pull out of some cities and possibly even allow Hadi’s return to office at the head of a transitional government — the first time the Houthis have offered such a concession. A prisoner swap involving thousands of fighters is also scheduled to take place before Ramadan begins June 5. Meaningful progress has yet to occur, however, even though small-scale exchanges have taken place. If the peace talks in Kuwait grind to a halt, the Houthis have made it clear that they will move forward with the formation of their own government.

Yet the peace talks have not faltered, though many of the thorniest issues — the formation of a transitional military and of presidential councils to oversee the handover of power, to name a few — will not be decided for months. And as Ramadan begins, the tempo of negotiations and fighting on the ground will slow to a crawl.

March 9: A Small Truce in a Larger War

The Saudi-led coalition is creeping toward Sanaa, hoping to hold the high ground before mustering to retake the rebel-occupied capital. They are now around 10 kilometers (6.2 miles) from Sanaa International Airport. From there it is only 8 kilometers to the city center. Emirati media is already heralding the start of “Operation Free Sanaa,” citing various tribal meetings meant to bolster support for the coalition in the capital.

Yemeni President Abd Rabboh Mansour Hadi, based out of Aden, appointed Brig. Gen. Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar as his armed forces deputy commander in late February. Hadi hopes to use him to garner support from local tribes to compete with similar efforts by Hadi’s opponent, former President Ali Abdullah Saleh and his Houthi allies. Al-Ahmar has a longstanding rivalry with Saleh but is also a polarizing figure within the tribal landscape. Thus, his support could just as easily backfire.

There are signs that Hadi’s advance is working. Republican Guard units loyal to Saleh have reportedly ordered the withdrawal of forces from Ibb, Dhamar and Al Bayda — located southeast of Sanaa — and have redeployed these troops to fortify the city’s defenses.

The drive toward Sanaa has been a slow march generally favoring the Saudi-led coalition. But in Taiz and Marib districts, the results have been mixed, and coalition opponents have had numerous successes. Allied Houthi and Saleh forces attacked Saudi Arabia’s Sahn al-Jen military base in Marib, reportedly killing and injuring dozens of soldiers. Fighting and Saudi airstrikes continue in Taiz, and coalition forces are still engaged with al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula across the south.

Saudi airstrikes have continued in the cities of Bani Hashish, Nihm, Al Ghayl and Hairan. However, major airstrikes in Sanaa city have not been reported in a week. Additionally, a Houthi delegation crossed the Alab port, without the accompaniment of pro-Saleh forces, for a Saudi prisoner swap that traded one Saudi for seven detained Yemenis. Talks are also allegedly taking place between Saudi representatives and the Houthi delegation for a partial cease-fire along the border to allow humanitarian aid to pass. This will not extend anywhere else in the country.

The border cease-fire negotiations have conspicuously excluded representatives of Saleh’s forces. This could mean one of several things. It may indicate that the Houthis and the Saudi coalition are considering a plan that would cut Saleh and his loyalists out of the future of the country. The Houthi-Saleh union was always a marriage of convenience and has been showing cracks as the Saudi coalition approaches Sanaa. The former president’s goal is to fully restore the control over Yemen that he lost in 2011. The gulf states in particular oppose such an outcome, as do many Yemenis resentful of his oppressive rule. The Houthis would not lose a great deal were they to surrender. They would likely return to their stronghold in northern Saada, with the Saudi stipulation that the tribal group halts cross-border aggression and tolerates Hadi’s government. That Houthi and coalition interests can mesh does not mean that a separate peace is imminent but that negotiations could have some success in shaping a future that is palatable to one major wing of the rebel movement, albeit to the detriment of the other.